Every sub-culture believes their people are better than the bozos on the outside. Skateboarders have a notable tendency towards exceptionalism. We collectively fail to distinguish between good and terrible skate art. We believe authority should leave us be, whether we are respectful or pig ignorant towards other users of public space. If we see the world differently, with unique expectations of life, work and the city – is this potentiality ever realised? If it isn’t, we may as well be any other group of beer-chugging jocks.

Almost half-way through 2017 and the world is still chain-barfing 2016’s dirty pint, exhausted by elections that serve only the politicians who call for them. If we engage (and you should engage… please vote), it is more out of habit or forlorn hope than genuine belief that things can change for the better. Optimists see hope in the millions galvanised to protest, choking up airports to make Islamophobic travel bans unenforceable, filling town squares to hear a man that looks a bit like Obi-Wan Kenobi speak of good, old-fashioned socialism. But we’ve been here before. Although hyper-capitalism has failed in its pledge that each new generation will be better off than their parents, its Randian high priests still sit at the very top of the hill. The sadly departed cultural critic Mark Fisher, known by his blog moniker K-punk, noted: “From the G20 protests, to the millions marching against the Iraq war, to the Arab Spring, to the short-lived student campaign against fees in the UK – the narrative of evental politics since the late 1990s has been reliably repetitious. Euphoric outbursts of dissent are followed by depressive collapse.” Big acts of resistance fail because we cannot imagine any serious alternative to the current way of things.

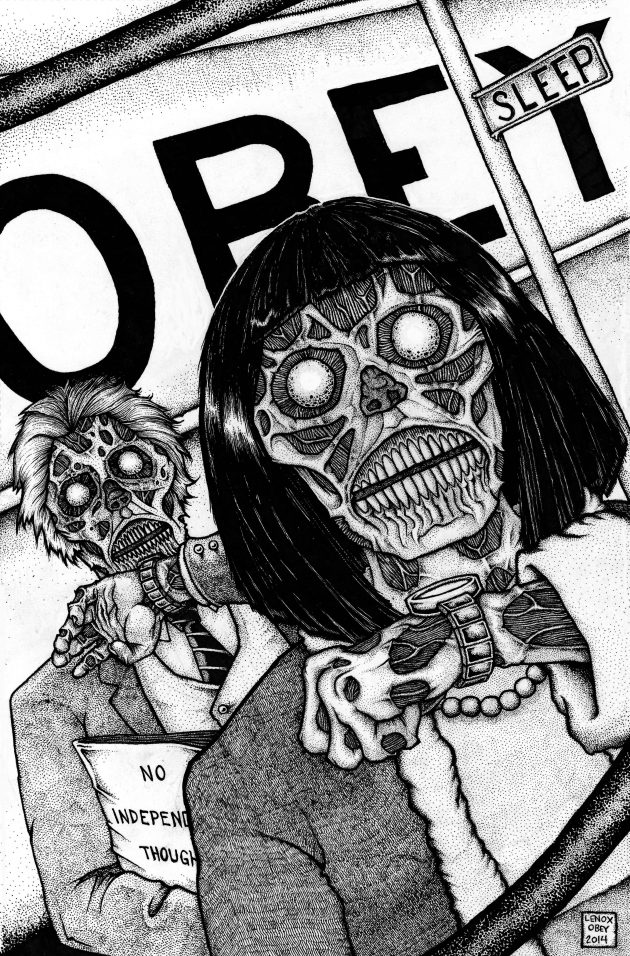

Illustration: Jason Lennox.

I was too busy failing to broaden my flip repertoire through the early 2000s to pick up on the radical thinkers that clustered around Fisher, and am now reading their ideas on ‘hauntology’ with neophyte zeal. This describes a state in which, with no impetus to create anything genuinely new, we are haunted by past visions of the future. Nagging memories of how things should have been are whispered by the ghosts of the 1960s, when man dreamed of space travel and the vast, imposing architecture that brought the modern to the everyday. In contrast, today’s pop culture, politics and economics recycle the past in ever more rapid loops. Baggy-as-hell, light-ass-denims are back, y’all. We are detached spectators, ironically curating, rather than actively reshaping our lives.

I was too busy failing to broaden my flip repertoire through the early 2000s to pick up on the radical thinkers that clustered around Fisher, and am now reading their ideas on ‘hauntology’ with neophyte zeal. This describes a state in which, with no impetus to create anything genuinely new, we are haunted by past visions of the future. Nagging memories of how things should have been are whispered by the ghosts of the 1960s, when man dreamed of space travel and the vast, imposing architecture that brought the modern to the everyday. In contrast, today’s pop culture, politics and economics recycle the past in ever more rapid loops. Baggy-as-hell, light-ass-denims are back, y’all. We are detached spectators, ironically curating, rather than actively reshaping our lives.

Skateboarders are avid consumers and hoarders. We commodify nostalgia’s warm snuggle. But skating is also all about practice over theory: playfulness and participation, which has the potential to be radical (in both senses of the word). We inhabit the city and the everyday with piss and vinegar, and yet, in the most urbanised century in humanity’s existence, still wait to have politics done to us – buffeted along by the story instead of framing the narrative. Long Live Southbank helped change this, doing what Surfers Against Sewage did for surfing in the early 90s: taking responsibility for our environment with an infectious energy and globe-spanning visual language.

I hate Trump, May, Farage and their ilk more than the generation of failed ‘moderates’ (read neoliberal ideologues) they usurped, and am truly terrified for the future. Although most big fights feel lost, despite what the entrail reading of recent UK election polling may suggest – now is exactly the time for little, local and everyday actions that can help push humanity’s stalled jalopy back onto the Enlightenment’s journey towards new and better. Skateboarders can do, and are doing, more to be part of the resistance: these are four things to start with.

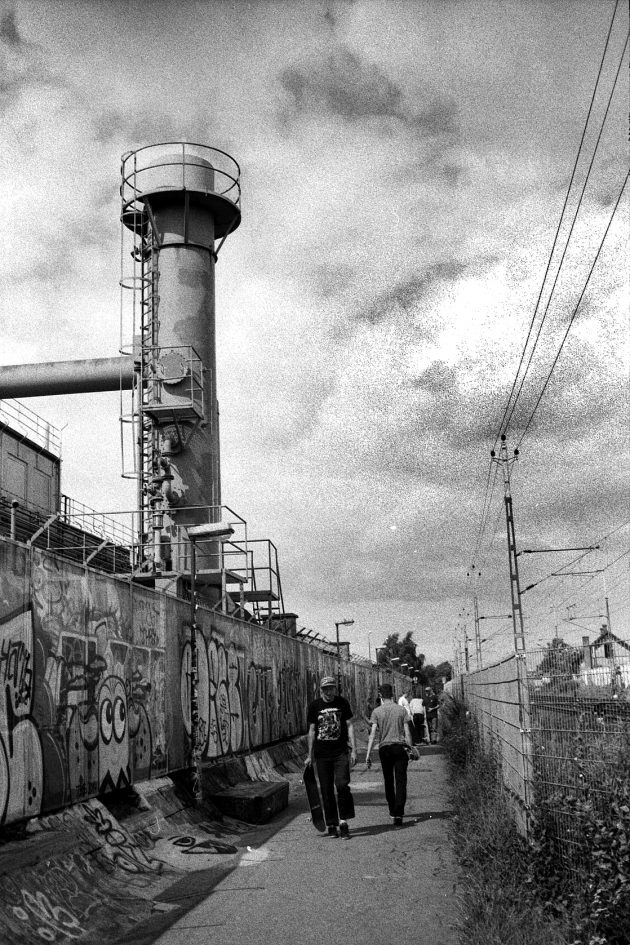

SKATE THE STREETS, ALWAYS

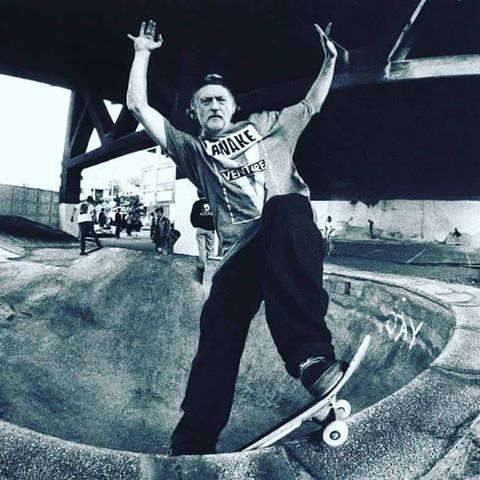

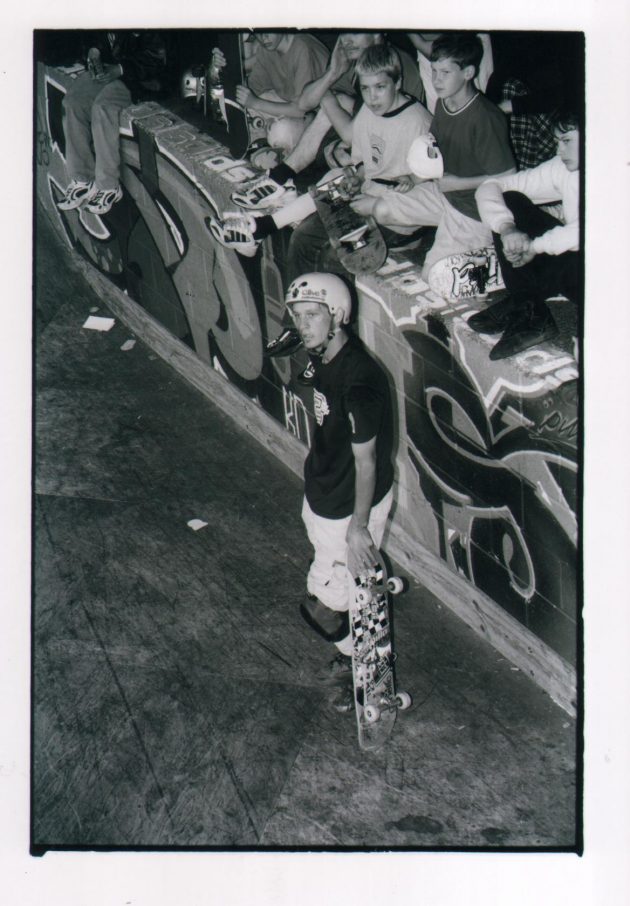

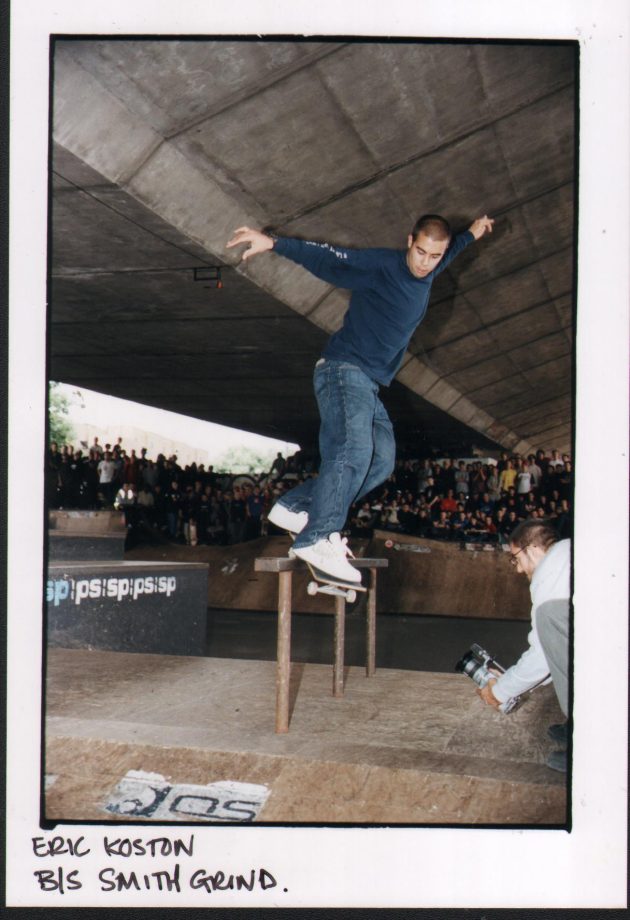

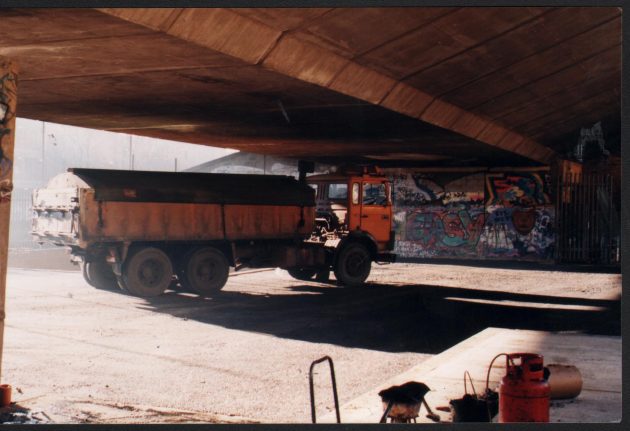

Skateboarding imbues the city and our leisure time with purposes beyond consuming or spectating. On Swedish radio, Sidewalk’s Ben Powell and Skate Malmö’s Gustav Svanborg Edén declared skateboarding “inherently political”, which made me want to high-5 the pair of them. Street skating claims our ‘right to the city’ in an age of privatised space and demonstrates, in public, what the human body is capable of in an age of sedentary work and leisure. We know this to be true since the opening frames of ‘Welcome to Hell’, and know in our bones when we are 17 years old, but forget by 35. In an interview with Sidewalk, one of the coolest fucking things I’ve read came from Andy Wood, the owner of Endemic, Huddersfield’s skateshop. In his 40s with a young family, he skates fast, pops over handrails and describes skating the streets as a responsibility for older skaters: how can we complain that the kids, with their abundant and accelerating skillsets, never leave the park if scene elders don’t set an example? By continuing to street skate alongside real-life responsibilities, we change what it means to be an ‘adult’ – and no diggity it needs changing.

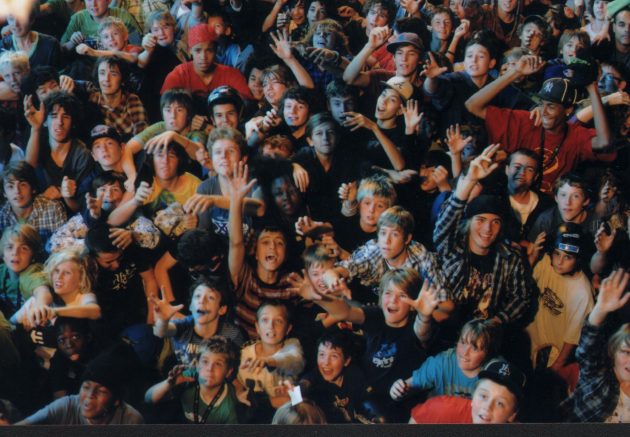

In the EU Referendum and US Presidential election a generational chasm opened to leave poor Wile E. Coyote flailing in the air. The media characterised those who voted to turn the clock back as old, white and resentful of an unknowable future, whilst the young, who by and large voted differently, were smug, consumerist, over-educated ‘metropolitan elites’ (who simultaneously can’t afford to pay rent). Mainstream sport is little help, separating coaches from sullenly obedient players and audiences from participants. In skateboarding, kids shred with salty seadogs old enough to be their parents. Ordinary sports, or Britain’s inefficient and hierarchical businesses (where senior managers fail to say “hi” to lowly co-workers), remind you just how potentially powerful our little world can be.

In the EU Referendum and US Presidential election a generational chasm opened to leave poor Wile E. Coyote flailing in the air. The media characterised those who voted to turn the clock back as old, white and resentful of an unknowable future, whilst the young, who by and large voted differently, were smug, consumerist, over-educated ‘metropolitan elites’ (who simultaneously can’t afford to pay rent). Mainstream sport is little help, separating coaches from sullenly obedient players and audiences from participants. In skateboarding, kids shred with salty seadogs old enough to be their parents. Ordinary sports, or Britain’s inefficient and hierarchical businesses (where senior managers fail to say “hi” to lowly co-workers), remind you just how potentially powerful our little world can be.

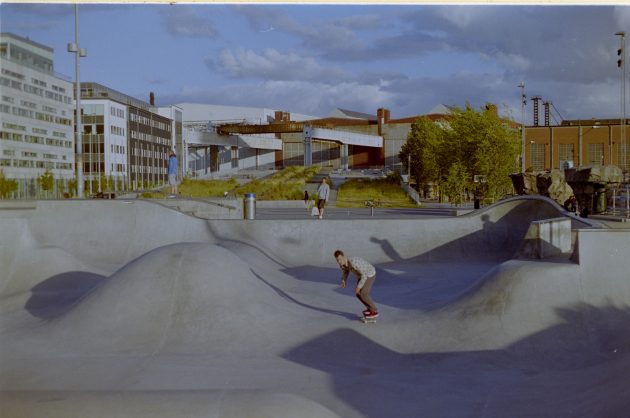

If you want to see the sort of respectful negotiation of space no longer valued in the UK after 40 years of “there’s no such thing as society” (Thatcher) or, if society does exist, it’s “broken” and we are somehow to blame (Cameron), go skate a Scandinavian city or read our article on the scene in Malmö. Street skateboarding produces authentic, inclusive and active urban spaces, which we must negotiate with people of totally different ages, occupations and interests (in contrast to being penned in skateparks with people just like us). Every time you disprove the prejudices of a pedestrian, you win a small victory that reverses the erosion of our collective social capital. If we’ve given up on education being primarily to “make a man ethical” as Hegel believed, we can bring a small part of his ideal classroom to the sidewalk: by not being dickheads, and not ever quitting.

SUPPORT YOUR LOCAL

Thousands of words have been written on the role of skateshops as youth clubs, first and last sponsors, community hubs and cottage production lines transforming civilians into skateboarders. We can all agree on their importance, but have no idea how to save them.

If Lost Art can run aground, the challenges facing the Skater-Owned-Shop look insurmountable. Liverpool One (a new generation of sinisterly clever neoliberal shopping centres, erasing the line between high street and private property) forced independent retailers from the centre. Then rents soared as the rest of the city gentrified and the fickle patronage of Nike turned to Janoski-stacked JD Sports and Sizes. Mackey sees future survival in terms of fundamentally re-thinking what a skateshop is for: back to hardgood basics and building links with other local independents – bars, tattoo parlours, book and print stores. Similarly, legendary Athens ripper Vassilis Aramvoglou has kept Color Skates running amidst Greece’s recession and sovereign debt crisis, focusing on similar fundamentals and building a relationship with a local bicycle courier to provide their sole means of goods delivery, sacking off tech utopians like Deliveroo (blinkered to the misery they bring to a precarious labour market) and keeping scarce wealth circulating between firms that genuinely support their city.

If Lost Art can run aground, the challenges facing the Skater-Owned-Shop look insurmountable. Liverpool One (a new generation of sinisterly clever neoliberal shopping centres, erasing the line between high street and private property) forced independent retailers from the centre. Then rents soared as the rest of the city gentrified and the fickle patronage of Nike turned to Janoski-stacked JD Sports and Sizes. Mackey sees future survival in terms of fundamentally re-thinking what a skateshop is for: back to hardgood basics and building links with other local independents – bars, tattoo parlours, book and print stores. Similarly, legendary Athens ripper Vassilis Aramvoglou has kept Color Skates running amidst Greece’s recession and sovereign debt crisis, focusing on similar fundamentals and building a relationship with a local bicycle courier to provide their sole means of goods delivery, sacking off tech utopians like Deliveroo (blinkered to the misery they bring to a precarious labour market) and keeping scarce wealth circulating between firms that genuinely support their city.

But this is still less than half the solution. We punters need to earn our mates’ rates: organise events, art and photo shows and video nights, think how your business, employer or townhall can work with your local SOS. In Huddersfield (again), an assortment of tweakers self-publish Achezine, drawing on skills and facilities from the town’s higher and further education establishments, working on an exhibition, a bespoke ‘no-comply’ lager brewed by the independent next door, and a film premiere in Huddersfield’s lovely Victorian shopping arcade: locating Endemic within the heart of its community. Or Boston’s Orchard, who worked with like-minded social enterprises to keep a free-to-use skatepark running through the harsh Massachusetts winter. Once upon a time, in proud industrial towns, customers, workers and owners came together as cooperatives. With never-ending austerity promised by an Old Etonian from a golden chair, our cities are not going to be regenerated beyond the fire-sale of social housing and green spaces and token ‘creative quarters’ that are often anything but (see Southampton). Shop staffers and lurkers who moan about their scene, as the till rusts shut, need to stop seeing themselves as ‘just’ a shop or ‘just’ customers.

START SOMETHING

The West worships the entrepreneur: on TV and in the Whitehouse. Skateboarders have marvelled at Rocco’s saga for 20 years. But while the wider world reveres modern day robber barons as ‘job creators’, the only jobs skateboarding creates in any volume are in retail or yet more sponsored skateboarders. The production of skateboards – luxury items which are predominantly purchased in the world’s richest countries – survives not through differentiation, but on the lowest possible marginal costs. Economists warn that competing on price alone results in a ‘race to the bottom’, jobs hemorrhaged to low cost countries that tolerate shittier labour conditions (a practice that is in turn threatened by Trump’s protectionism, to the benefit of no one except perhaps the Chinese or Mexican workers who may end up in less stupid industries).

As in decades past, the indie start-up has changed and enriched the face of skating. Soccer-mom friendly logo boards are a minority amid weird, cool and beautiful offerings from Polar, Magenta, Hopps, Scumco, Welcome, Weekend, Evisen, Blast, etc. etc. But we’re still failing to visualise how this can benefit actual skateboarders. Some who’ve recently disrupted the market, like Bronze’s Peter Sidlauskas, counsel others to “just work the job you hate.” I can sympathise with wanting to pull up the drawbridge, but this is terrible advice. It assumes markets are fixed in size (think of the ubiquity of Palace, trading to kids with no prior exposure to skating), illustrating what economists call the ‘fallacy of the lump of labour’. The number of jobs is not finite: a newly employed person spends money, creating the need for more jobs, and so on (btw this is also the best way to shut down your racist uncle midway through his seasonal “coming over here, taking our jobs” rant). More urgently, such thinking keeps late capitalism dependent on bullshit, low pay, debt-subsidised jobs in a bloated service sector. If you have an idea, for pity’s sake run with it, for the good of us all. The internet enables you to launch from your bedroom, with minimal risk, whilst keeping up the 9 to 5. In the face of permanent global depression, skaters taking a punt at something new will provide them job satisfaction (and skills acquisition) and help kill pointless, precarious work.

Most importantly, your thing doesn’t have to be a board brand or Instagram-driven streetwear bollocks. Surely this is not the limit of our imaginations. Collect boards, do you? Think about what Deckaid has done, exhibiting skate geeks’ collections to aid youth-based charities. Have a massive magazine stash? Rent them out to your local shop. Think you and your mates have skills, enthusiasm and patience? Look what Ash Hall, or John Cattle, or Paul Regan have done with different iterations of socially-entrepreneurial skate schools. Know some artists/are one yourself/know a distributor? Check out these dudes and their ‘refugees welcome’ board project.

All this can be linked together and scaled up. There’s a good chance funders will listen, but they need something tangible to listen to. For that, my friends, you need to organise. If you go to their skatepark consultation, their ‘active in the city’ event, you’re reacting. We can set the agenda. A rabble of voices gets drowned out: but a lean, focused machine that can access and direct resources is hard to ignore. Bryggeriet/Skate Malmö as well as LLSB show us that this doesn’t have to equal endless committee meetings and ‘county council rrrradical’ faux-graffiti branding. They can be super cool, inclusive, and get things done. If you want to link and grow your projects, protect your DIY or streetspot, get a new park built, access charitable and public funding, and eventually employ other skaters in meaningful work, organising is key, and skateboarders tend to be terrible at it.

In the UK, you can get free advice from your local Community and Voluntary Service. Then you have several choices. You can stay small (limited to £5,000 per year) but start tomorrow with a Small Charity Constitution. To do bigger things (including holding premises and employing people), you can become a Charitable Incorporated Organisation (CIO) or a Community Interest Company (CIC). A CIO is more attractive to funders, but must be approved by the Charity Commission, who will then monitor you closely. A CIC can be created rapidly and is lighter on the paperwork, but may be less attractive to big funders like the National Lottery. And when you start something, and it grows: remember why you did it. Even if you can earn a living purely selling boards and t-shirts, you can still be more than ‘just’ a board brand – take Real skateboard’s projects with Humidity and Uprise shops in support of the American Civil Liberties Union.

MAKE WORLDWIDE CONNECTIONS

Magenta say it, and they mean it. Who would have thought Bordeaux, with its cobbley-ass streets, would be a destination? The end game for all the above – filling in forms, busting your ass skating and filming – is to put your city on the map, boost your scene and making the world a better place. The biggest of big pictures is that this helps roll back the creeping nativism stoked by right-wing demagogues and the tabloid media across the world. Sixty-five percent of the French electorate can’t hold the line on their own. If big politics tells us that internationalism is a thing of the past – what of all of us brought up to think globally? Prime Minister Theresa May told those who “believe you’re a citizen of the world” were instead “citizens of nowhere”. Let that sink in for a moment: millions of us, the first in our families to stay on in education post-16, who went on school trips and took GCSE French, who were told by careers advisers to imagine working anywhere on earth, who have quite literally done what we’ve been told, are now “citizens of nowhere.” Fuck right off, Theresa May: a sense of internationalism is one of the few things neoliberalism gets right.

Luckily, nationalism and skateboarding are not productive bedfellows – and we can do more to unlock the power of this. Skater-led NGOs have brought skateboarding’s unique ability to engage young people to Afghanistan, Palestine, South Africa and Myanmar, alongside projects building or repairing skateparks in quake hit Australia and Native American reservations. And doing something closer to home doesn’t mean limiting your international horizons. Bruce Springstein, proud son of New Jersey and global traveller, says, “My localism is something I want to use as a strength, rather than something to get away from.” A great example is the Rios crew, putting Budapest on the map by skating and filming in a distinctive way, all whilst xenophobic, nativist strongman, Viktor Orbán, increasingly locks Hungary into an imagined past where everyone looked and felt the same.

Without trying to, the Rios guys have delivered one of the clearest rejections of everything Orbán, and May, and Trump, and Le Pen, stand for – and skaters the world over journey to Budapest to share this with them.

Written by Chris Lawton

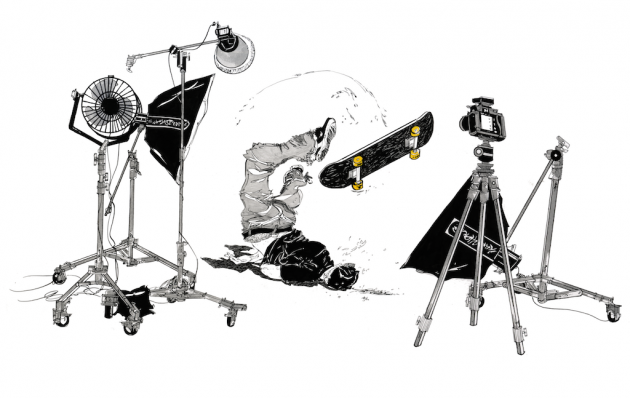

Illustration by George Yarnton

If you would like to write for Crossfire we are looking for a news editor and two feature writers. Get in touch here.

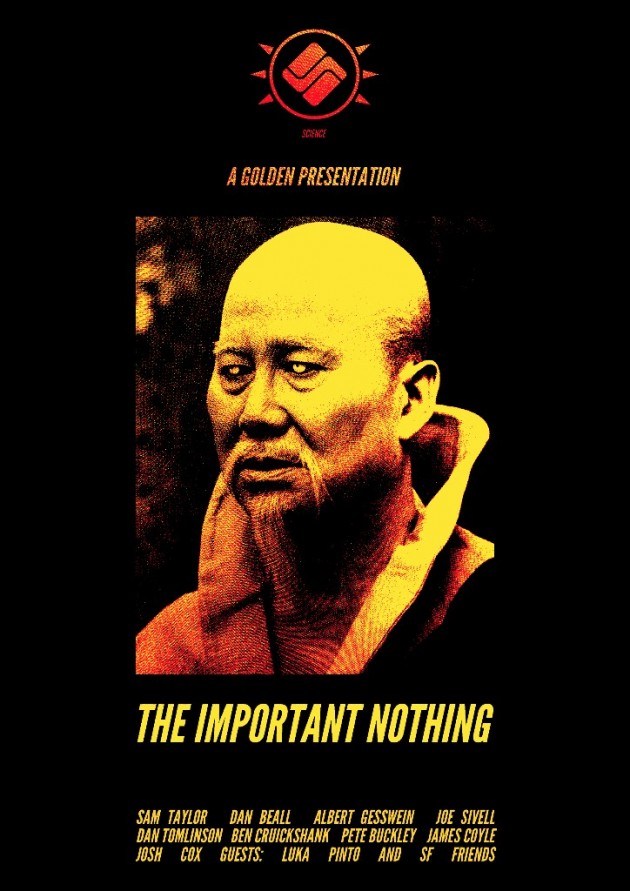

Been waiting for this since the film premiered. Jerry Hsu needs no introduction, just pure good vibes. Click play to see what went into his MADE Chapter 2 part.

Been waiting for this since the film premiered. Jerry Hsu needs no introduction, just pure good vibes. Click play to see what went into his MADE Chapter 2 part.

Magenta‘s latest edit comes from the land of fresh weed and waffles. Join them as they cruise around Amsterdam’s streets for their latest collab with Pop.

Magenta‘s latest edit comes from the land of fresh weed and waffles. Join them as they cruise around Amsterdam’s streets for their latest collab with Pop. The CPH Open hosted another barrage of sick skating and cold beer. Here’s Thrasher’s account of the week.

The CPH Open hosted another barrage of sick skating and cold beer. Here’s Thrasher’s account of the week.