Simon Bernacki frontside wallrides the TBS DIY. Photo: Tim Smith.

For skateboarders in the Northern Hemisphere, the start of the year can feel like the end of the world. An existential and meteorological downward spiral, deepened if you spent last summer somewhere markedly better. But then trips are excitedly planned across chaotically duplicate social media platforms through April and May; a glut of adventure from June to early September; then the stomach-tightening disappointment as nights lengthen and tarmac dampens. The cyclical woe ramped right up in 2016. Brexit’s ‘fuck you, footloose citizen of the world’ followed by the fever dream turned reality of President Donald J Trump make escape more necessary than desirable.

What if, in 2017, we took something back from our travels, improving our hometown environments, the rest of our active lives and the lives of younger generations? Last summer, my friends and I visited Copenhagen and Malmö for the third time. This year, it would be nice to reduce the contrast between away and home. Fortunately, the relatively small Swedish city provides a lodestar for UK skate scenes demoralised by generational churn and municipal hostility. Most impressively, Malmö’s skaters have demonstrated what we already know to be true: skateboarding is an incredible tool for creating and maintaining active and engaging public spaces, a free spectacle for participants and bystanders, encouraging a sense of shared-ownership over the city and its public realm. Politicians in the UK invest millions trying to ‘engage’ young people, to encourage a sense of community, to increase physical activity, and to bridge the generational divide – skateboarding does all this for free.

Zombie Stu getting some at Steppeside DIY. Photo: Simon Bernacki.

Malmö is a modern skateboarding phenomenon. The 2016 final of the Vans Pro Skatepark Series was not hosted in sun-kissed California, but in a frequently rainy upper corner of northern Europe. The city features in videos from sportswear giants, ordinary Joe’s and several documentaries (with a school within the indoor skatepark attracting particular interest) and is, of course, headquarters to Polar Skateboards. Copenhagen, over the bridge, attracts attention for similar reasons: huge, well-designed public skateparks, indoor parks and global events; flourishing DIY scenes; rippers attracting the biggest of sponsors; and energetic cadres of long-time skaters who have convinced their local authority of the wider benefits of all of this.

Malmö is a more unlikely story than the Danish capital. It’s much smaller – similar in size to Nottingham. It also experienced the sharp-end of de-industrialisation and the fragility of neo-liberal redevelopment. Just as Nottingham lost thousands of skilled blue collar jobs with the fall of textiles and heavy industry in the 1970s and 1980s, Malmö’s largest employer, shipbuilding, went into free fall. Both cities looked to the financial and business services for a ‘knowledge led’ recovery. This proved just as vulnerable to global headwinds, as Malmö was particularly hard hit by the Swedish Financial Crisis of the early 1990s. A visitor from the North of England in the mid-1990s would have observed familiar symptoms of urban blight.

Now, five years after the Occupy Movement and nine years after the Global Financial Crisis, Malmö is an optimist’s poster child for intelligent and inclusive regeneration. And, would you believe it, skateboarding has played an important role. Malmö’s development (aided by small things like building a university and a bridge to Copenhagen) is due to more than skateboarding, but when investment ran in, the local skaters were already at a sprinting start. With nowhere in winter other than an indoor carpark, they formed a club. As membership grew, the City took notice and provided an abandoned school for a mini-ramp, and then the much larger former brewery site for an indoor park, and the non-profit Bryggeriet was born. Competitions built capacity such that, when the Council agreed to support a ‘destination’ skatepark to spearhead the regeneration of the old ship-building area, Bryggeriet worked with a team from Portland to ensure user expertise nibbled into the marrow of the project. The result was the incredible Stapelbäddsparken, which drew Quicksilver to relocate the Bowlriders European Cup in 2006. By this time, Pontus Alv had released his first video, ‘Strongest of the Strange’, broadcasting to the world that parks and events were the tip of an iceberg that encased a street and DIY scene, which in turn helped kickstart the global proliferation of the ‘crete-and-hope’ ethos, as well as the verb “to charge”.

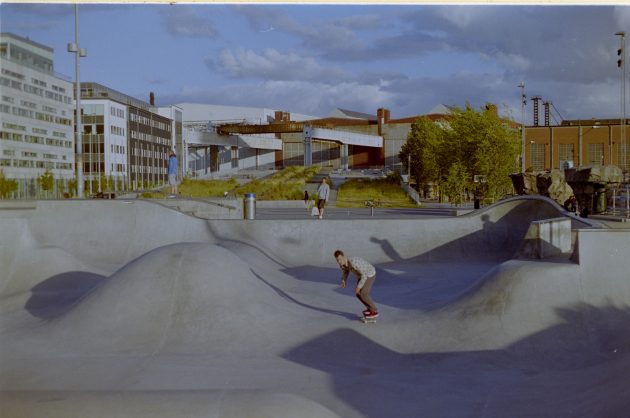

The wonderful Stappelbadsparken park shot by Andrew Cullen.

When Quicksilver withdrew from skateboarding, Bryggeriet together with the City took over. Malmö’s annual Ultrabowl was given a budget to: “put Malmö on the map, and help develop a relationship with the skaters for other projects.” Even more incredibly, the Council considers skateboarding within its strategy to ensure public spaces are well used, and co-brands Skate Malmö with the skaters. Among other things, Skate Malmö officially encourages skateboarders to visit the city, something that eluded Philadelphia in Love Park’s heyday as a global skate magnet.

Forensic skate archivists will trace much of the above to Phil Evans’ ‘Coping Mechanism’ and recent interviews with Gustav Edén, one time Unabomber rider and now Skateboard Coordinator for the City of Malmö. Gustav was generous with his scarce time and responded to our questions, exploring factors that may enable British skaters to have the confidence and sense of agency to act on Malmö’s inspiration.

The foremost questions are: can lessons from Malmö be applied in the UK? Is hard work and a can-do attitude more important than the serendipity of living in progressive Sweden? Malmö City did not always regard skateboarding so favourably, once seeing it in similar terms to many UK Local Authorities: a ‘nuisance’; young men making noise and wasting time. Gustav argues that Malmö’s skaters’ attitude and ambition were as important in changing perceptions as the successful hosting of global events: “the City supported the development of the skate-organisation and helped it grow. The City gave skaters a chance. That’s half the story. Perhaps more crucial… is that the skaters here realised they had to be a good partner to the City. They realised they had to give the city value for their investment.”

Our experience in the UK is often characterised by Local Government hostility (in Kettering, Norwich, Birmingham, Sheffield and other towns and cities where bans have existed for years or have recently been implemented). However, we have to be honest and admit to often choosing a passive role. We lobby councils to pay for skateparks; we launch online petitions to fight bylaws and save skatespots. Rarely do we tell the town hall what we will do in return… and then go out and deliver it. Though successful skater-led UK campaigns often argue that skateparks may reduce anti-social behaviour, or increase physical activity – little is usually done to ensure that “may” becomes “will.” There are many brilliant exceptions, such as Frontside Gardens, the work of John Cattle and Wight Trash, Ash Hall and Sheffield’s Skateboard School, and, of course, Long Live Southbank.

I’m generalising, but the point stands and Gustav concurs: “Skate organisations often (not always) forget to shift the focus to what they can do for the city and how this can help them grow, rather than just thinking about what the city can do for them. The skaters in Malmö have been a strong, driven partner for the city. For a community development department, this is a godsend. Someone wanting to do something and actually being able to deliver. That is a crucial part of the Malmö story.”

A common fear is that officialdom inevitably ruins the cool of skating, wrecking the credibility of skaters amongst their own communities. We are currently struggling with this trade-off in Nottingham. I found myself farcically misquoted in our local newspaper, “jump up” instead of “kicker”, alongside the depressing old chestnut placing street skating within the gamut of anti-social behaviour – when skateboarding is the most supportively ‘social’ thing in most of our lives. In skateparks we socialise with people exactly like us, rather than negotiating space with other users of the city. If 2016’s tale of political and social upset is one of old against young and the educated against the left-behind, actually sharing space and interacting with different kinds of people is more important than it’s ever been.

Notts crew at Steppeside. Photo: Andrew Cullen.

Malmö’s skaters learned that hosting events ordinary people could appreciate and engaging with the public via skate schools actually benefited the core scene: “The idea from Bryggeriet has always been to deliver above the expectations of the City, as well as staying true to the skate scene.” Perhaps it’s the Scandinavian tendency to approach even the most casual thing with an enviable mix of extreme seriousness and whimsy, but the proof is in the pudding. Malmö has one of the corest, most aesthetically fucking cool scenes on earth – not just the best known company, Polar, but also Post, Hats, Details, Poetic Collective and the visual output of Bryggeriet and Skate Malmö themselves (helped by master-videographers-in-residence like Phil Evans). The skaters have managed to nurture a successful, expansive and civically-minded ‘skate destination’ and grow a cool-as-all-hell sub-culture. Gustav described global events like the Vans final as “the result, not the instigator” of this year-long scene.

This has wider impacts for the arts and youth culture. We spoke to Street Lab skateshop big-popper Rasmus Sjölin, who told us a little about the social buzz the Malmö skate scene produces. Even relatively little things like a DIY build at the famous TBS spot can end in a street party spilling from the bar round the corner from Street Lab, whilst local hotels, shops and venues all recognise the benefits visiting skaters bring. Gustav added that the type of person attracted to the characteristics of skating (not a team sport, unstructured, intergenerational) can have a genuinely life-changing experience that leads to connected interests and skills from “a network that permeates every walk of life in the city.” And for older people already sold hook-line-and-sinker, the rich skate scene attracts them and their families to move to the city – bringing their skills, interests and creative ideas. The OG street spot now on my ‘favourite on earth’ list after several afternoons this summer, known as ‘Svampen’ by the locals, is overlooked by Malmö Art Centre, directly illustrating these permeations.

Malmö Harbour. Photo: Simon Bernacki.

As a counter-balance to encroaching ‘sportification’ from the Olympics and the sportswear brands, Malmö’s skaters have ensured that their events emphasise the cultural crossovers of skating, with Ultrabowl and the Vans championship being closer to city-wide music or art festivals, rather than singularly big corporate events. The Malmö scene has also helped pioneer the greatest antidote to dumb-ass, alpha males: as many women and girls are encouraged to skate as possible, and then those who get good are supported – just as you would with male skaters. Recent upstart brand Poetic Collective proudly support Sarah Meurle front and centre in their team: in the UK only Lovenskate have the guts to strongly back (fellow Kalis obsessive) Lucy Adams. And power to them: it’s (early) 2017 people – the 1950s live on only in Trump’s inner circle of porcine Breitbart comb-overs.

We’ve so far skirted around the biggest of big things: Malmö’s advocacy of the positive role of street skating. This provides a real-life example to accompany the theory that street skating uses public space in an engaging and inclusive way, contributing to a town or city’s “collective symbolic capital”: the things that make it unique and attractive. Visitors aren’t drawn to the ten-a-penny high-street (unsurprisingly in terminal decline), where the design (and merging) of public and commercial space explicitly steers them towards either retail or work in Iain Borden’s analysis, but to imaginative, lively spaces created by the people who live there.

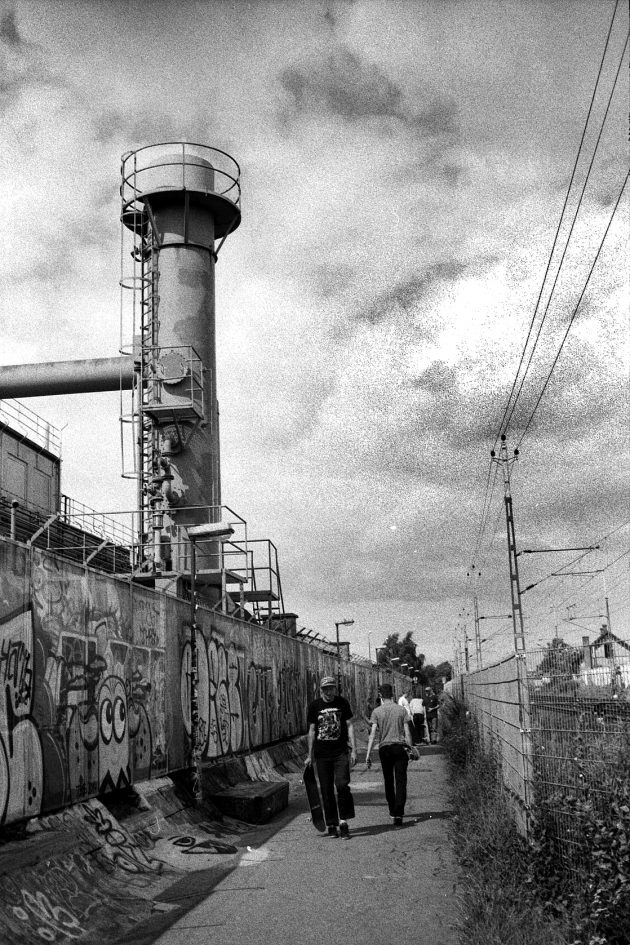

TBS DIY in all its post-industrial glory. Photo: Simon Bernacki.

Ocean Howell demonstrated this in the tragi-comic story of Philadelphia in the early 2000s, whilst warning that skaters could become the unwitting foot soldiers of gentrification, useful in reclaiming unutilised space but ultimately expendable when the fruits of their labour raises the real estate value. A more sustainable situation, where skaters are neither vilified or exploited – where they are “good partners” to the city – is the long game Malmö seems to have nailed. From recent news that Hull aims to be the UK’s first genuinely skate friendly city (designing street skating into, rather than out of, new public space), it is perfectly possible in our hometowns too. But Kettering shows that the reverse can still happen. A punitive townhall seals the generational divide in law: not only does skateboarding in Kettering carry a £1,000 fine, being younger than 18 during certain times is similarly punished. Hull, European City of Culture in 2017, says to its residents: “this city is yours, activate it.” Kettering instead opted for inevitable population ageing and the calcification of civic space.

This isn’t just about skating, it’s about positive micro-action. The unspeakable horror of Big Politics in 2016 may continue all the way into 2017 if Marine Le Pen’s resurgent National Front aren’t stopped at the ballot box. The urban theorist David Harper, in calling for a new fight for our collective ‘right to the city’, remarks that, “while big fights might seem unwinnable, small victories can lead to bigger ones.” In Gustav’s view, skating’s success in Malmö has been part of the city’s wider success as a place to live, be young and grow older. If we want our hometowns to benefit us economically and socially, we need to stop seeing skateboarding in separation. In times of tight local budgets, our cities need us as much as we need them.

Written by: Chris Lawton.

Thanks to Rasmus Sjölin, Skate Malmö, Bryggeriet, Gustav Edén, Phil Evans. Watch Coping Mechanism on Vimeo OD.

Photo thanks to: Andrew Cullen, Simon Bernacki and Tim Smith.

This final photo is Chris putting in work to film Nottingham’s Elliot Maynard for a killer line in ‘Crows’ Feet‘. Photo: Andrew Cullen.

Get inspired. Collaborate, think, plan, lobby and transform your hometown.